30″ November “2022

Cape Town, South Africa – It was early December 2021 and infections from a new coronavirus variant, Omicron, were ripping through South Africa, where 90,000 people had already died from the pandemic.

COVID-19 cases had surged 255 percent in one week among a population in which only 24 percent was fully vaccinated and the country had hit a high of nearly 27,000 new infections daily.

On a windy Monday morning, Dr Caryn Fenner drove the half-hour from her gated community to her workplace, located in an outer industrial suburb of Cape Town. Her pale blue Fiat 500 was the only vehicle driving along motorways lined with powerlines and two-storey warehouses, each the size of a football field, housing coffee manufacturers, freight companies and steelmakers.

Fenner, who is the executive director at Afrigen Biologics & Vaccines, was racing to meet a tight deadline for a locally produced mRNA vaccine. Her facility, tucked between other warehouses selling water filtration systems and spare motorcycle parts, looked unremarkable. Yet revolutionary work was being undertaken inside its boxy clinical rooms. Afrigen was using publicly available information to make its own trial version of Moderna’s COVID vaccine.

When, on November 26, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) named Omicron a variant of concern, within hours foreign governments imposed travel bans on half a dozen African countries, including South Africa.

The economic impact was immediate. Shares on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange fell almost 2 percent by midday, and the rand traded at its lowest in more than a year

South Africa itself had alerted the WHO about the variant after scientists from Botswana had detected it among travellers who flew in from Europe. The South African foreign ministry slammed the bans. “Excellent science should be applauded and not punished,” it said.

The travel ban had knock-on effects at Afrigen. Equipment and chemicals critical to developing a vaccine were stuck abroad. The airline tickets of foreign scientists who were flying in to cooperate were cancelled as were those of staff due for training overseas. Grounded flights also delayed the sharing of laboratory samples of Omicron to aid faster research into the new strain. These developments almost entirely halted global scientific collaboration and set Afrigen’s research back by months

“That for me is probably the most important innovation that this hub and the scientists with Wits can do,” she adds pointedly. For now, the more immediate hurdle is to produce more of the replica vaccine, so human trials can begin in May 2023. Moderna told Al Jazeera that the company is already working on a next generation version of its shot that would be “refrigerator stable” for developing countries.

Long road for African tech

Vaccines were developed within a year of the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, but due to a bidding war with richer, Western nations, much of Africa was last in line for doses. Afrigen is the central hub of a pilot project created by the WHO to share know-how on making mRNA vaccines with “spokes”, or manufacturers, from more than 20 countries in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa, including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Tunisia. That decision was taken after manufacturers Moderna, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech declined to share their vaccine recipes. In South Africa, Afrigen will make the mRNA, and the Biovac Institute will manufacture the vaccines.

While the demand for COVID-19 shots will eventually subside, health experts say far more is at stake. African countries now import 99 percent of their vaccines and 70 percent of all medicines used, but the African Union has set a 壯陽藥 c-launches-partnerships-for-african-vaccine-manufacturing-pavm-framework-to-achieve-it-and-signs-2-mous/” target=”_blank”>goal for up to 60 percent of routine immunisations to be produced on the continent by 2040.

“The scientists we can get, they are sitting in universities,” Terblanche says. “But we need to train them to operate in a vaccine facility … and not academic research.”

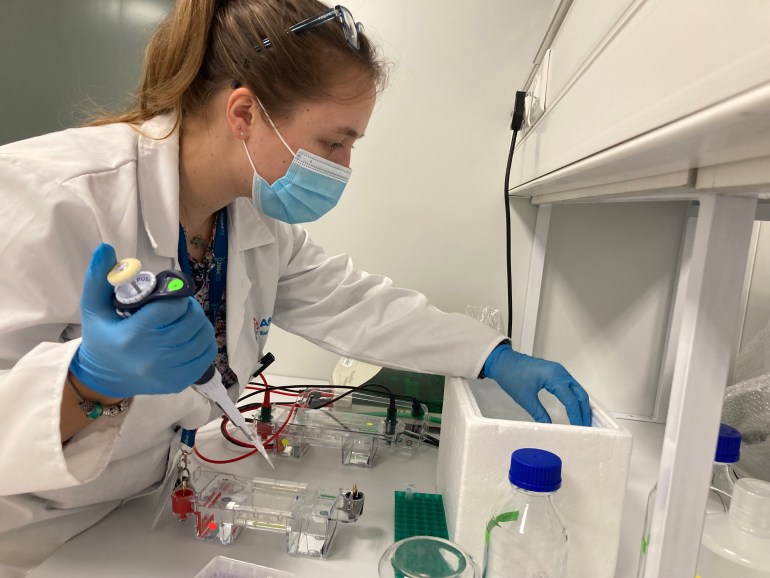

Take Frances Lees. The young scientist joined Afrigen in January 2020 just as the pandemic was getting under way. Lees had completed a master’s degree in cell biology and had been working on veterinary vaccine projects before being quickly pulled into mRNA development as one of the few researchers who had a background in molecules

Sometimes it goes wrong, and you don’t really know why and you have to repeat your experiment, so there’s a lot of process that goes on that takes time,” she says. “And time isn’t our friend at the moment.”

Lees believes a breakthrough would shatter a misconception that this kind of research and development cannot be done in Africa.

“Synthesising mRNA isn’t super difficult; it is trying to make sure that we have lots of it … at a quality high enough for a vaccine,” she says. “We are not going to skimp on raw materials or make shortcuts

In it together?

Dr Hapiloe Maranyane is relatively new at Afrigen, having started in April as a senior scientist. She stands alone in the laboratory suite, peering through safety glasses and grasping a single channel pipette dropper in one hand as she dispenses chemicals inside a biosafety cabinet. She opens her journal to a blank page and starts to take notes.

In commercial vaccine manufacturing, “it is not just the science that matters,” she says. “The biggest challenge for me was shifting from an academic focus to a manufacturing focus. There is definitely a higher stringency, as it should be, in terms of how you record your science and quality assurance that needs to be stratified and quality control.”